Xiaorui Huang

PS 378 Game TheoryFinal Essay

2012-Aug-24th

Grade: A+

Introduction

Climate

change has an international (or spatial) dimension[1]

and an intergenerational (or temporal) dimension. The international dimension,

framed by various studies as a tragedy of the commons involving different

nations, become the major perception of climate change in public and political

discourses (Raihani and Aitken 47-55, Wood 153-68). In contrast, the intergenerational

dimension of climate change, despite certain academic coverage, is largely

overlooked, which has some interesting implications on the solution to climate

change as a whole (Gardiner 408, Schuppert 303-06).

In

this essay, I firstly construct an extensive model of the intergenerational

game of climate change. Then, based on this model and game theory, I discuss

both negative and positive influences of the neglect of the intergenerational

dimension on addressing climate change as a whole.

The

Intergenerational Game of Climate Change.

Inspired

by a thought-provoking work of Stephen Gardiner, a scholar in environmental philosophy,

I construct the model of the intergenerational game of climate change based on

two temporal characteristics of climate change, namely resilience and deferral

(403). On one hand, climate change is resilient in the sense that it takes

decades for even a radical reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission to

transfer into the decrease of GHG concentration in upper atmosphere. On other

hand, the deferral of climate change means that our current global warming is

caused by the GHG emission produced decades ago and our current emission will only

affect the degree of climate change several decades later.

In

the intergenerational game of climate change, we assume generations do not

overlap and each generation is a player who wants to achieve both a good

economy and a decent environment[2].

Starting from the first generation, each player is firstly imposed an offer

from the previous generation (if any) and then coercively impose an offer to

the next generation. Players can either make a cooperative offer or a defecting

offer. If Generation A imposes a cooperative offer to Generation B, it means that

Generation A restricts its own GHG emission by slowing down its own economic

development. If Generation A imposes a defecting offer to Generation B, it

means that Generation A maintains the economic development and does not

restrict its GHG emission. To quantify, we set both initial[3]

economic value (EC) and environmental value (EV) as 10. A cooperative offer

adds 1 point to the EC values of the generation making the offer and adds 1

point to the EV value two generations

later. A defecting offer adds 2 points to the EC values of the generation

making the offer and deducts 1 point from the EV value two generation later. This two-generation deferral of the environmental

impacts of offers is to simulate the resilience and deferral of climate change

mentioned above. EC and EV values are cumulative and are inherited from earlier

to later generations. Finally, in this game, we consider EV=0 as a point of

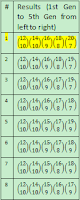

human extinction and the game will iterate until reaching this point. Figure 1

shows the game tree of the intergenerational game for the first 5 generations

with the EC and EV outcomes of each generation in each strategy-path in the tables

on the left.

As

Figure 1 shows, when isolating a single generation and its offer-making, the

outcome that this generation gets from making a defecting offer is always

better than the outcome from making a cooperative offer (e.g. for the 5th

generation, its outcome in Result #3 is better than Result #4). This is because

a defecting offer gives the generation that makes the offer an immediate 1 more

point on EC value. Meanwhile, both defecting offers and cooperative offers do

not influence the EV value of the generation that makes the offer. The economic

effects are immediate but the environmental effects are deferred. Therefore,

individual rationality makes each generation always prefer making a defecting

offer over a cooperate offer.

In contrast, collectively, most generations (except the

first several ones) prefer the cumulative outcome of everyone cooperating over

everyone defecting because a decent environment is also a goal other than the

economy. Furthermore, doomsday comes when EV=0. However, individual rationality prevents cooperation from happening. Therefore, the Nash Equilibrium for the intergenerational game of climate change is that every generation defects and mankind extincts at the 12th generation, which is represented by the all-red path in the game tree and the Result #1 in the tables.

Figure 1 with Result Tables

-

A Red line means a defecting offer;

a blue line means a cooperate offer;

-

The top numbers in the parentheses are the EC value and the bottom

numbers are the EV values.

-

From left to right, the five pairs of parentheses are the outcomes

for from 1st generation to 5th generation.

|

Of

course, limitations exist in this model due to its simplification and the

inevitable uncertainties of climate change. First, generations are not discrete

and they do overlap. Second, each generation lives on the planet for a

substantial amount of time before and after it takes charge (i.e. childhood and

old age). Third, we do not exactly know how many generations does it take to

reach doomsday if no generation restricts GHG emission. In other words, the

initial EV value and the quantification of the environmental impacts of offers

could be questionable. Fourth, after a certain degree of environmental

degradation, economic activities will be harmed, which is not shown in the

model.

Even

though certain academic effort has been done to reveal the intergenerational

dimension, it is generally neglected in public and political discourses. Such

neglect, partly manifested as the exclusive focus on the international

dimension, have negative implications on addressing climate change as a whole.

The

first negative implication is that it directs most political and academic

resources to address the international dimension whose solutions are

incompatible to the intergenerational issues of climate change, which crippled

the comprehensive (i.e. including both dimensions) mitigation of climate

change. Many studies have been done that seek for methods to encourage multilateral

cooperation to solve the international tragedy of the commons of climate change

(Gardiner 399-401, Raihani and Aitken 47-55, Wood 153-54). However, these

methods, which include both theoretical mechanisms like building reciprocity

and practical actions such as the United Nations Climate Change Conferences,

are inapplicable to the intergenerational dimension of climate change because the

bare co-existence of players in this intergenerational dimension (Gardiner 405).

Moreover, according to Fabian Schuppert, a scholar in environmental politics,

the three major schemes developed to mitigate climate change in the

international dimension, namely cap-and-trade schemes, carbon emission taxes, and

personal ecological space quotas, are ineffective in the intergenerational dimension.

Specifically, all three schemes are centered at equal mitigation burden among

all people (both intra- and intergenerational), which, given the scientific

uncertainties of climate change, conveniently provides current generation

excuses to push off its responsibilities and costs of mitigation of climate

change to future generations (Schuppert 308-17). Thus, with the solutions for international

dimension incompatible with the intergenerational dimension, the neglect of

intergenerational dimension cripples the comprehensive solution of climate

change.

Besides,

such neglect hides from public perception the institutional inadequacy of current

political structure, which lowers the bureaucrats’ and politicians’ expected

utilities for supporting GHG emission restriction and therefore impair the

political support for addressing climate change. The primary goal for

politicians and bureaucrats is to ensure being re-elected or promoted, which is

influenced by the public perception of their performance in their terms of

office. However, as discussed above, climate change is resilient, which means

that it takes decades (much longer than normal terms of office) for GHG

restriction to realize its effects. As a result, it is impossible for a

government to make perceivable mitigation of climate change within one term of

office, which is the institutional inadequacy of current political structure in

addressing climate change (Gardiner 403). If the public are aware of such

inadequacy, they are more likely to support a pro-GHG-restriction politician

whose policy appears to be ineffective in his or her term because they know it

takes more time. In contrast, if the public are not aware of such inadequacy, pro-GHG-restriction

politician are likely to have his or her policy be criticized as ineffective by

the public and his likelihood of being re-elected decreases. In other words,

politicians’ and bureaucrats’ expected utilities for supporting GHG restriction

decrease when the public awareness of the institutional inadequacy is low.

Since the neglect of intergenerational dimension hides the resilience and

deferral of climate change from the public perception, it also lowers the

public awareness of institutional inadequacy and therefore lower politician’s

expected utilities for supporting GHG restriction. Consequently, such neglect

impairs the political support for GHG restriction.

Positive

Implications of the Neglect of the Intergenerational Dimension on Addressing

Climate Change

The

neglect of the intergenerational dimension also has positive implications on

the solution to climate change, which is derived from its influences on the public’s

expected utilities on addressing and not addressing climate change.

Firstly,

such neglect may somewhat increase people’s expected utility of addressing

climate change by making people unaware of the deferral and resilience of climate

change, for such awareness undermines their will to address it (as shown in the

Figure 1). Specifically, while in mainstream discourse people do talk about the

long-term effects of addressing and not addressing climate change, the fact

that current actions, either restricting GHG emission or not, will not have

their impacts realized until decades later is blurred by the neglect of the

intergenerational dimension. Known from the game model, if people are fully

aware of the resilience and deferral of climate change, it is rational for them

to choose to maintain economic development but not restrict GHG emission. However,

the neglect of the intergenerational dimension make the public unaware these

two characteristics of climate change and therefore increases the public expected

utility of and support for restricting GHG emission and addressing climate

change right now.

Moreover,

such neglect, when manifested as the exclusive focus on the international dimension,

helps build a public perception that if we do not address climate change right

now, disasters will fall upon them very soon, which decreases the expected

utilities of not addressing climate change. Specifically, when focusing on the

international dimension, the current disastrous impacts of climate change are

highlighted. Such highlighting on disasters make people easily builds a direct

and immediate causation between what they are doing now (i.e. restricting GHG

emission or not) and what is happening (disasters happening or not). For

example, after Hurricane Katrina attacked America in 2005 (which is not

directly caused but closely associated with climate change), media coverage on

climate change suddenly rises in America (Everything’s

cool). In the year after, American public support for addressing climate

change reached the highest point in 2000s. If the public are well aware of the

intergenerational dimension of climate change, they should know that these

disasters are not caused by current GHG emission and will not be mitigated by

current emission restriction. However, the neglect of the intergenerational

dimension enables people to develop an immediate causation between climate change

and such disasters and make them less willing to leave climate change

unaddressed. In other words, such neglect changes their preference by lowering

the utility of not addressing climate change, which increase the public support

for addressing climate change.

Conclusion

The intergenerational dimension of climate change is

largely overlooked in political and public discourses. To explore this

dimension, I construct a model of intergenerational game, which shows a

devastating Nash Equilibrium of every generation keeping GHG emission high and

mankind rushes toward extinction. However interestingly, by changing the public’s

and politicians’ expected utilities of addressing and not addressing climate change,

the neglect of the devastating intergenerational dimension has both negative

and positive implications of the comprehensive solution to climate change.

Work Cited

Everything's Cool. Dir. Daniel Gold. Perf. Daniel Gold. Bullfrog Films, 2007. DVD.

Gardner, Stephen. "A

Perfect Moral Storm: Climate Change, Intergenerational Ethics and the Problem

of Moral Corruption." Environmental Values 15.3 (2006): 397-413.

Print.

Raihani, Nichola, and David

Aitken. "Uncertainty, rationality and cooperation in the context of

climate change." Climatic Change 108 (2011): 47-55. Print.

Schuppert, Fabian.

"Climate change mitigation and intergenerational justice." Environmental

Politics 20.3 (2011): 303-21. Print.

Wood, Peter. "Climate

change and game theory." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

1219.1 (2011): 153-170. Print.

[1] In

this essay, I use the term “international dimension” to denote the

intra-generational, spatial dimension of climate change because in a single

generation, addressing/not addressing climate change is generally considered as

interactions among different countries.

[2] In

the intergenerational game of climate change, the term “environment” and its

quantitative value EV introduced later only refers to climate change. A higher

EV value represents a LOWER degree of climate change and a BETTER environment;

vice versa.

[3] Historically,

the initial values could refer to the status right before the first industrial

revolution